Editor’s note: This piece was written by our very own member, Publicity Coordinator, and Ombudsman, David Tschanz. David is an epidemiologist, and a historian. Fascinating perspective for the very times we’re in.

The Plague of the Spanish Lady

By David W. Tschanz

In August 1918 while World War I raged from Finland to Mesopotamia an epidemic began. In two months it covered the globe, sparing only Tristan da Cunha in the extreme South Atlantic. No one has ever figured out how it traveled such great distances in so short a time. Coast Guard search parties, for example, discovered Eskimo villages in remote, seemingly inaccessible locations wiped out to the last adult and child.

Most of its victims were young men aged 18 to 45. Many of them went from perfect health to the coldness of the grave in less than a day. It crippled troop movements, slowed the reinforcement of Pershing, broke the already fragile German morale and shattered the Kaiser’s war effort.

Only the Black Death of the 14th Century and the Plague of Justinian of the 6th Century, would rival it in the rate it claimed human lives. Neither would match it in its speed.

Only the Black Death of the 14th Century and the Plague of Justinian of the 6th Century, would rival it in the rate it claimed human lives. Neither would match it in its speed.

In four months it would make the death toll from the greatest of all of mankind’s wars till that time look like a beginner’s course in death and destruction. Nearly three times as many American soldiers would die from it as from enemy action in the same space of time. Virtually all of the deaths among American sailors in World War I were from the disease or its sequel, pneumonia. By the time the Armistice was signed on November 11th, the epidemic had disappeared. In its wake it left behind, by conservative estimates, at 27 million dead — including an incredible twelve million dead in India alone. It had a number of names: “the plague of the Spanish lady”, “Spanish influenza” or “the grippe”.

Most people simply called it “influenza.”

What is Influenza?

Influenza is a viral infection of the upper respiratory tract characterized by sudden onset, cough, chills and high fever. In some cases it can pave the way for a secondary bacterial pneumonia. Strictly speaking there is no such thing as “gastrointestinal flu” by the way. “Flu” is by definition a respiratory illness and the involvement of other organ systems simply does not occur.

“Flu seasons” are characterized by an increase in the number of respiratory illnesses. Given enough time, these seasons generally decrease in severity as those stricken developed increased immunity to the disease. Minor changes in the antigens produce minor variants or “strains” through a process known as “antigenic drift.” These new strains can infect persons immune to last year’s strain, but because of the developed immunity the attacks are generally less severe than the year previous.

Influenza however, has the unique ability to undergo something called “antigenic shift”, essentially a radical mutation of the hemaglutannin and neuraminidase spikes on the outside of the virus. When these shifts occur previously developed antibodies provide no protection against the virus. As a result antigenic shifts, which seem to occur after ten to fifteen years lead to severe flu epidemics as that experience in the “Hong Kong flu” in the 1950’s, the “Asian Flu” of the 1960s and the “Russian Flu” of the 1970’s. (The names are assigned on the basis of the location of the laboratory that first isolates the particular strain). In 1918 such an antigenic shift seems to have occurred

The First Wave

The place of origin of the pandemic of “Spanish influenza” (the name derived from the belief in some countries that the disease had originated in Spain) has been a matter of question because there were, in fact, two outbreaks of influenza in 1918. The first reports came from Fort Riley, Kansas following a three day dust storm, though what role, if any, the dust storm played is unknown. The first cases reported to the base hospital, a 3068 bed capacity facility on the morning of March 11, 1918. By noon 107 cases had been hospitalized, by the end of the week 415 more had joined them. This initial wave was milder than that which would start in August. Similar illnesses were reported that spring among the troops in Europe. The epidemic appeared in Japan and China. It too was mild and called “3-day fever” or “wrestler’s fever” in addition to influenza. The spring wave was not highly diffusible or widespread. It reached only limited areas of Africa, largely missed South America and had little impact in Canada. Despite the large number of sick, the disease claimed few lives. But by no stretch of the imagination, except among the morbidly apprehensive could it be considered a harbinger of what was to come.

The Second Wave

By mid August, almost simultaneously throughout the world, influenza returned in a more virulent form. On August 28th, sailors entering Boston harbor brought the disease from Europe where it was just starting to spread to the United States. Within a matter of days influenza had spread along the entire East Coast. Some of the sailors on the first Boston shipment were transferred to Michigan and Illinois and became the nuclei of spread of influenza in the Midwest.

Among the civilian population in the United States — certainly the least war torn of all the combatants, the enormous impact of the epidemic is carried in dry statistics. In one week in October, 4500 died in Philadelphia and 3200 died in Chicago. As the epidemic spread, health officials in many cities closed meeting places such as schools, churches and theaters. Public gathering were prohibited in Washington where the Supreme Court suspended its sessions. At the same time in the capital, undertakers were stationed at the doors of hospitals to remove bodies as fast as the victims died. It was a necessary, if ghoulish decision, every hospital bed in the city was occupied.

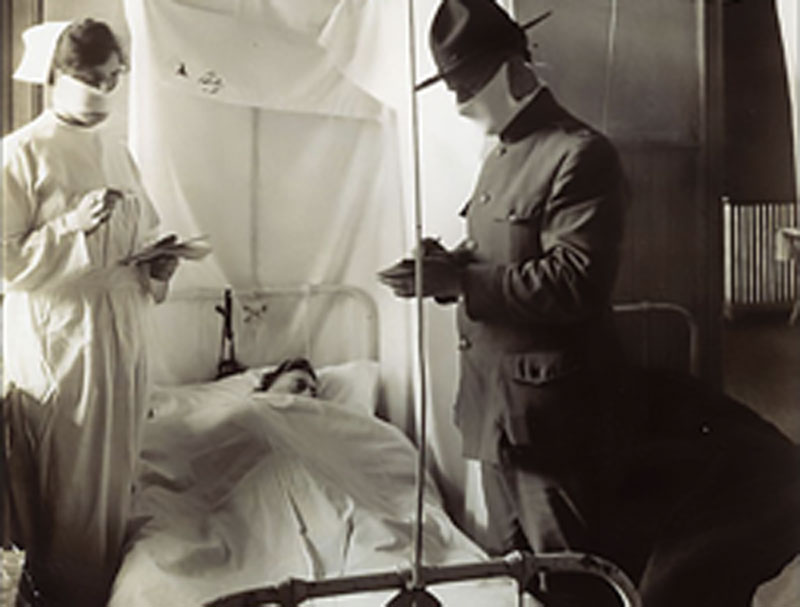

Ordinances were passed making it a crime to cough, sneeze or spit in public or to be outside without a face mask. Bodies piled up in city morgues where conditions became so offensive that “veteran embalmers recoiled and refused to enter.” Public services were reduced. Police and fire departments were shrunk to critical size by the disease. Sanitation workers and streetcar conductors, office clerks and others personnel caught the “flu bug.”

The New York Times urged its readers not make unnecessary phone calls because 2,000 of the city’s telephone operators were out sick.

Cruelly ironic, the pandemic paralleled the war in carrying off mostly the young and the strong. Young fathers and mothers were felled in droves. In one week in October 19 of 42 new mothers in a San Francisco maternity ward died of influenza. Yet during the outbreak the death rate for those aged 45-74 remained where it had been before the epidemic.

The Military

Throughout the country the crowded army camps where men were training for overseas service made inviting targets for any epidemic disease. Influenza stalked through these camps, striking down victims right and left. The Army Medical Corps had never seen such an appalling amount of sickness.

At Camp Devens, where 30,000 men were quartered, the base hospital, possessing a maximum capacity of 2500 beds soon had 8000 patients. These figures were typical, across the United States, as at the height of the Meuse-Argonne offensive, one out of every five soldiers in the United States was stricken with the disease. Immediately effected was the ability to reinforce Pershing, as the epidemic raged unabated in the United States, draft calls for October and November were cancelled.

Pershing’s urgent appeals for needed reinforcements were answered by Army Chief of Staff General Peyton March: “If we are not stopped on account of influenza which has passed the 200,000 mark [of ill soldiers], you will get the replacements and all shortages of divisions up to date by November 30.”

Military life at an increasing number of camps had decelerated to a fevered crawl. At Camp Dodge, Iowa, the surgeon for the 19th division in formation, was compelled to convert one barracks after another into contagion wards. His problem: how to fit eight thousand sick into a two thousand bed hospital.

Camp (now Fort) Meade, Maryland was counting 1500 new cases every twenty-four hours. More than 11,000 soldiers — one fourth of the complement in the first week of October were “too sick to readily distinguish night from day. At Camp Grant, near Rockford, Illinois, 10,173 soldiers, one-third of the population, were sick.

On October 13, Marsh updated Pershing with more bad news: “The epidemic has not only quarantined nearly all camps but has forced us to cancel or suspend nearly all draft calls. Continued shipments (of troops) are consequently draining reservoir of men in this country. “

March was summoned to the White House where Wilson discussed the dilemma with him. To ship the men and pack them into troopships, both men knew, might result in the deaths of thousands. But Pershing needed men. At the same time Max, Prince of Baden had appealed to Wilson for an armistice. The Germans were losing the battle of the Meuse-Argonne and finally seemed to be cracking. Wilson had to estimate the effect on the enemy’s faltering will to fight should the Germans suddenly learn that the pressure was off, that the flow of American replacements had ceased.

March was blunt in his appraisal — continue the shipments. “Every such soldier who has died [from influenza] has just as surely played his part as his comrade who has died in France. The shipment of troops should not be stopped for any cause.”

Wilson agreed with March grimly — the reinforcements would continue. Then, just as March was about to leave, Wilson eyes brightened and he astonished the Chief of Staff by reciting:

There was a little bird,

its name was Enza

I opened the window

and in-flu-enza

Children were spouting the same bit of rhyme all over America that grim fall. Pershing could only watch the numbers of casualties from the battle and the flu mount. He did not need to have March lecture him on the effects of influenza. He only need look at his own troops.

The American Expeditionary Force (AEF) was suffering from the pandemic as badly as it had from the German army. Over 16,000 men new men reported sick in the week of October 5th alone, over two-thirds of them from the troop ships bringing reinforcements.

As the 26th Division prepared to take its place in the front line halfway through October, influenza swept its ranks. On October 14, Brigadier General Richard Shelton was forced to give up command of the 51st Infantry Brigade. Every battalion and company in the division lost officers and men hitherto considered indispensable. Then, bereft of leadership and a third of its key personnel, the 26th moved into the maelstrom that was the Meuse-Argonne offensive.

The pandemic snarled attempts to reinforce the divisions already in battle, and no division took part in the Meuse-Argonne battle for more than a few days without needing the reinforcements Pershing fruitlessly continued to plead for. Influenza reduced one replacement detachment of 500 en route from the coast to a paltry 278 by the time it had arrived at Revigny.

The 91st Division, in the line from September 26 to October 1, had to make do without the services of 5,000 replacements designated for it because they were all in quarantine in Revigny. Another problem made worse by the flu was that of evacuating the disabled from battle to hospital.

In wartime, evacuation is at best difficult. The fighting in the Meuse-Argonne sector produced 93,160 wounded in the American First Army between September 26th and the end of the war. These casualties had to be moved to the rear along broken, muddy roads and through traffic jams that stretched the full length of these roads. Added to this was the completely unexpected complication of 68,760 cases of influenza or secondary complications of the disease like pneumonia and bronchitis.

In the French sector things were no better as influenza continued to assail all armies. Throughout 1918 prior to the second wave, no more than 25% of those evacuated from the French Army at the front had been sick rather than wounded. From September to the end of battle, as many men were being taken off the line because of influenza as due to wounds.

The crisis of the pandemic in the First Army occurred during the second phase of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, which took up most of the month of October. As the casualties mounted so did the number of flu cases. The pandemic, if it did not stop military operations, slowed them perceptibly. It depleted the number of troops available for combat and support and it threatened for a while to disrupt the evacuation system and to overwhelm the hospitals completely.

The medical corps of the armies of both sides had been geared to deal with a slaughter. Now they had to contend as well with an epidemic which doubled the numbers of those requiring treatment. Nor could the flu be ignored as a “minor illness”. Of the 100,000 stricken in the AEF over 8000 died. The overall mortality rate among those developing pneumonia of 32% was an average only –in some units, as Pershing wrote –“It reached as high as 80%”. On September 28, the 57th Pioneer Infantry Regiment of the 31st Division was struck — three days later 200 had died. While wounds were not communicable, influenza is, so in the vortex of chaos and death, ambulances drivers and hospital aides were ordered always to segregate influenza cases from the wounded. But drivers under artillery fire didn’t quibble about diagnoses as the litter bearers shoved their burdens in the back. So the wounded were exposed to the disease which often hastened their deaths.

The co-incidence of the pandemic and the Meuse-Argonne offensive created enormous overcrowding. When the offensive began, the First Army was already 750 ambulances short of predicted need. But hospital capacity was equal to the anticipated need. Then came the pandemic and the facilities were swamped. As an example Base Hospital Number 6 in Bordeaux had 4319 patients, in spite of an official capacity of 3036.

These statistics make no allowance whatever for the fact that a hospital’s capacity to care for patients decreased dramatically as hospital personnel succumbed to the flu virus themselves. Base Hospital Number 41 reported 15 of its 38 medical officers sick and half of its nurses and corpsman stricken. On October 19 the University of California medical unit in France buried three of its corpsman who had died of flu. Seven of its fifteen doctors were sick and the remaining eight had 2000 patients — flu cases in extremis and wounded. On October 23rd, two more corpsman died and another trainload of sick and wounded arrived.

By mid-October as the fighting proceeded unabated, 9549 US soldier had died in combat; 7328 had died of the flu. In the previous twenty four hours the disease had claimed 889 lives. The death toll, while appalling, is probably understated, because only the deaths primarily due to influenza or pneumonia are attributed to it.

To fully appreciate its effect, it is necessary to consider the pandemic as a secondary cause of death — i.e. it is necessary to consider how many deaths primarily ascribed to wounds or gas should secondarily be blamed on the pandemic. How may wounded died in their holes, lying in the rain and waiting for shelter all because the whole evacuation system was clogged with an unanticipated number of flu victims

The Navy

Aboard ship things were worse. The Coast Guard cutter Seneca dragged into Gibraltar from Plymouth, England with only one officer well enough to stand watch –Lieutenant Charles Armstrong — the ship’s surgeon.

The Navy Patrol vessel Yacoma moored in Boston with 75 percent of her complement in sick bay.

In Rio de Janeiro, Captain George B. Bradshaw led an honor guard of bluejackets and Marines as they led a long row of coffins borne of flimsy donkey carts to old and richly foliaged San Francisco Xavier Cemetery. There the bodies of 58 sailors and Marines who had died in eight days were laid to rest. Aboard Bradshaw’s command, the cruiser USS Pittsburgh 674 others – over half the crew — were too ill to get out of bed.

A few days later more than a hundred of these, facing lengthy recuperations, were placed aboard the British transport Vauban and taken to New York. The Pittsburgh had been put out of action as effectively as though shelled at Jutland.

The experience of the Pittsburgh was typical. The Navy had been hurt worse of all the services. More than 120,000 officers and men of the entire 500,000 naval service personnel had been stricken. Five thousand died of influenza — ninety per cent of US Naval losses in the war — more than twice the losses suffered by both sides at Jutland.

The Germans

For a few days the pandemic helped shore up the hopes of Ludendorff, Hindenburg and the Kaiser that there was some possibility of survival for their armies. At lunch on October 1st the Kaiser expressed his belief that the flu would somehow cripple the Allied armies while leaving his own relatively unaffected. But presently the reality of thousands of sick German soldiers on the Western Front and long lines of hearses filing out of Berlin swept away this last ditch illusion.

Within days the Germans were having much the same troubles as the Allies, but the statistics on what was happening to their armed forces, badly bloodied and yielding ground everywhere are much harder to come by. On October 17 Ludendorff acknowledged that influenza was raging in the German front lines. He attributed its lethal nature to the absolute weariness of his army — “A tired man succumbs to contagion more easily than a vigorous man.” The news was no surprise to the people of the war-torn nation. Already suffering from starvation, despair, revolution and impending defeat they were now ravaged by the “Blitz Katarrah.”

Hardly a family in the country was spared as the sick lied in their beds, shivering with fever and racked with coughs. There was no medication to help them. In Hamburg four hundred died each day and furniture vans had to carry the bodies to the cemetery.

In Berlin, the imperial capital, the shops had next to nothing to sell –rubber, paper, cotton, leather, textiles and clothing had disappeared. Worst of all was the shortage of food. “If one looks at the women,” wrote one medical officer, “worn away to skin and bone, with seamed and careworn faces, one knows where the portion of food assigned them has really gone.” Yet even with their mother’s rations, the children were “thin and pale as corpses.” Unto these people the scourge of influenza fell. On October 15th over 1700 died in Berlin alone. By the end of the epidemic over 400,000 civilians had died.

The broken and despairing army was struck in the same way as the enemy. Influenza gummed up the German supply lines and made it harder to advance and harder to retreat. It made running impossible, walking difficult and simply lying in the mud and breathing burdensome.

From the point of view of the generals it had a worse effect on the fighting qualities of the army than death itself. The dead were dead and that was that, they were no longer assets but neither were they liabilities. But flu took healthy men and turned them into delirious staggering wrecks. Their care in turn diverted healthy men from other important tasks and effected morale. Few things could be more disconcerting to a front-line squad than a trench mate with a temperature of 104. The Kaiser’s armies, already reeling, lost more men that they could not afford to lose. Germany sued for peace amidst death. The Armistice went into effect on the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month.

The Aftermath

With an irony that surpasses comprehension, the epidemic faded almost simultaneously with the ending of the Great War. It seemed almost as though mankind were being taught a lesson as to who really reigned supreme in the giving and taking of life. Four years of dogged conflict had killed twenty-one million, the pandemic killed at least twenty-seven million in a few months.

In all history there had never been an onslaught of swifter death from disease. The Black Death and the Plague of Justinian had killed a greater percentage but they had taken years to do what influenza accomplished in weeks.

In the United States, the final reckoning was 548,452 lives lost. Nearly eighteen times as many Americans died from the pandemic as died from a year and a half of warfare. The 1918 death rate per 100,000 was 588 — a mortality rate this country has never approached before or since. In the single week of October 23, 1918 21,000 Americans died — the highest mortality toll ever recorded in America at any time for any cause before or since.

In the same week 2700 American soldiers, at the height of the bloody Meuse-Argonne offensive died “over there.”

A year and a half of war had cost the United States Army some 34,000 dead due to combat. Two months of the pandemic had claimed the lives of 24,000 soldiers and 5,000 sailors. Britain, France and the other Entente powers lost proportionately the same number of men. Harshly neutral, the disease struck the Germans just as savagely and as brutally, providing neither side with a military advantage.

The pandemic did not alter the course of history on the level of organizations or institutions — collectivities. The Germans, broken by other factors, were essentially doomed to the onrushing defeat headed towards them that fall. Had the pandemic not come they might have been able to hold out a bit longer, but then again Pershing and the other Allied commanders would have gotten all their reinforcements. In either event the end result would have been the same.

Yet nothing that sweeps away 548,452 young American men and women in a matter of weeks can be said to have had no influence on the history of the United States. Nothing that claims the lives of twenty seven million can be said to be without impact. It is however much harder to gauge what that influence was.

It is as if someone had randomly poisoned the punch served the graduates at the 1918 West Point commencement exercises. Such an act would have affected the military history of World War II but in a way that defies logical analysis. It is a matter of never-ending and frustrating speculation as to assess what “might have happened if.” The task is made harder in that most of the victims were the young, the promise of their potential not yet reached for society is structured to keep those under forty from having considerable power. Only one head of state died — the King of Spain. Few other significant political or public figures over 35 were afflicted, but their children died in droves –labor leader Samuel Gompers’ daughter died, French Premier Georges Clemenceau’s son succumbed as did the sons and daughters of Senator Albert Fall and Turki bin Abdul Aziz; Ibn Saud’s oldest son and designated successor. For others it was close friends and protégés who teetered on the verge of death, their promise yet unfulfilled.

Josephus Daniels, the United States Secretary of the Navy was himself barely touched. But he watched with deep concern as his 36 year old Assistant Secretary and protégé was carried off the troopship Leviathan on a stretcher, too ill with influenza to walk. The young Assistant would develop double pneumonia and was considered likely to die. A seemingly insignificant event, and a man whose death would probably not affect the course of history. But to Daniels’ joy the young man survived, and Franklin Delano Roosevelt went on to other things.

Originally published in Command Magazine #16 (1991)

Thanks for this writing. I found it arresting that the sudden death paralleled the fighting and war — with military taking the hardest hit. I think, as you say, indeed it was a lesson as to Who reigned supreme with regard to the giving and taking of life. As if, if you’re going to prefer killing (in a world-wide conflict), I’m going to join in that, and give that to you. The fact that it ended just that quickly, with the signing of the Armistice, is very sobering to me.

This is both a fascinating and terrible story. How did that pandemic manage to spread so thoroughly, when people weren’t nearly as mobile as they are now? Was it carried on the wind? By birds? In the end, how effective was social distancing? Did social distancing change survival rates or just delay the inevitable? Why did it target young men? Why was there a second wave? Will there be a second wave of the current pandemic? If there is, will it be more lethal? Will we have food shortages too?

Terrible indeed. People were dropping as they walked. This is like something out of a sci-fi movie. How indeed, did it spread? I looked up the island that David mentioned, Tristan da Cunha; it’s in the middle of the ocean between South America and South Africa. Why a particular age group? That’s curious to me as well. This one has very different age profiles than that one — the children were largely untouched, but young adults were very much in the center of this. That’s curious immunology.

Social distance was implemented even back then. This is primarily why, of the two cities, St Louis fared much better than Philadelphia, which ended up with some 4,500 dead in a very short period of time. Both had gotten the warnings; Philadelphia ignored them–at least until it was past time. Concerning a second wave, I think this is inevitable. We will be in whatever degree of separation for however long; and safely to say, people will get weary of this, and begin to come out, the first yellow or green light they get. That won’t mean it’s passed, just passing. I.e., it will still be out there. And as soon as people begin to congregate, it’ll re-spread. One account I read on this predicted a June/July peak, with secondary peak in November. Yikes. Concerning more virulence? I would expect (unless, God forbid, it mutates) that the virulence will be no worse, but that “herd immunity” will have begun to occur as well, as people begin to recover. I had this discussion with a friend, concerned with smelling peoples’ cologne on a bike trail, that it may actually be beneficial. A minuscule exposure would work to inoculate perhaps.

On food? Wow. One of the greatest risk I now see in any emergency is people. If they brainlessly cleared out shelves of toilet paper (for which it wasn’t even warranted) what will they do for food. Scary.